Research

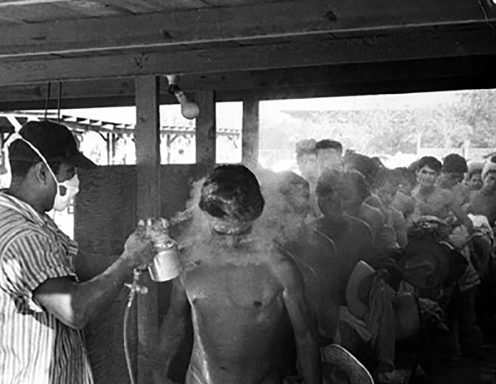

My research focuses on the history of food, agriculture, and labor in the context of U.S.-Mexico relations throughout the 20th century. In particular, I have looked extensively at the U.S.-Mexico guest worker agreement known as the Bracero Program that ran from the early 1940s to the mid-1960s. Alongside the co-occurring Rockefeller Foundation-funded Mexican Agricultural Program, which was the first project in what would come to be called the "Green Revolution," Mexican food and foodways began a period of immense transformation.

My earlier research on the interaction of these two programs explored how they combined to disrupt the lives of the peasant farmers (campesinos) and their families. By taking away laborers, the Bracero Program placed undue burden upon their wives and daughters who were left to pick up the slack. Meanwhile, the Green Revolution programs forced these same families to spend what little money they had on new fertilizers in order to compete with and grow new varieties of corn and wheat. This research was published in the journal Agricultural History in 2021.

My dissertation project, "Modern Agricultures, Traditional Diets: Braceros, Campesinos, Food, and Foodways, 1940-1965," in contrast, focuses more on the direct effects to diet and identity among these same groups, as well as the transformation of the urban diet in Mexico as rural communities migrated to seek incomes there. This research answers important questions about the connection between food and identity among Mexicans/Mexican Americans, as well as exploring one of the most dramatic transitions from traditional agriculture to "modern" techniques.

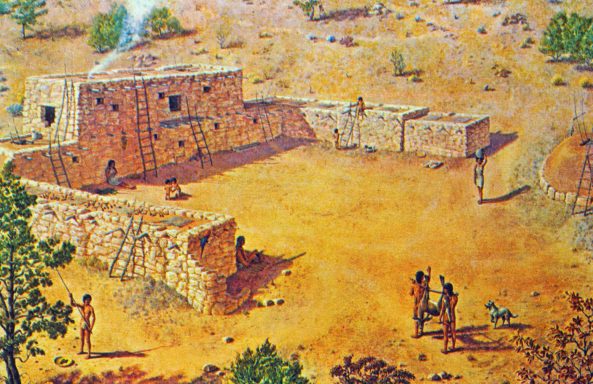

In addition to writing about modern agricultural history, I have done extensive research on Indigenous groups of the U.S.-Mexico border region, including the Tohono O’odham, the Pueblo, and the Rarámuri. My studies of these groups has been concerned with the changes made to their foodways and agriculture from the Spanish Colonial era to the present, and with their interactions with surrounding mestizo and foreign populations during the 20th century. I was invited to present some aspects of this research for the Amerind Foundation in 2017 and again in 2021.

All of my research shares a general theme of revolving around questions of food and identity. The Indigenous practice of companion planting three particular crops (maize, beans, and squash), for example, remains a staple of subsistence farming in many parts of Latin America, even while consumption of beef, wheat, and other European-introduced foods has proliferated among middle and upper classes since the first Spanish colonizers arrived in the Americas.

Across the world, food has always been tied to identity. As French gastronome Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin wrote in 1825, “Dis-moi ce que tu manges, je te dirai ce que tu es” (Tell me what you eat, and I will tell you who you are). This was (and is) a common sentiment in the Spanish colonies that would become Latin America. Many exonyms for Indigenous peoples were rooted in observed eating practices. Spanish colonists projected their identity by maintaining a particular diet (see Rebecca Earle's The Body of the Conquistador: Food, Race and the Colonial Experience in Spanish America, 1492-1700).

Untangling the complex web of these food histories and their legacies for Latin Americans (especially those Latina/os living in the U.S., where processed foods and fad diets abound) is central to my work as an academic, while celebrating this heritage with the community is fundamental to my role as a public historian.

© 2023 mxleyva. All rights reserved.